Full description not available

K**S

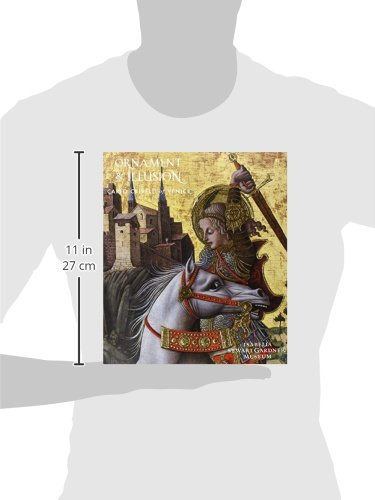

Carlo Crivelli at the Gardner Museum

There could hardly be a more appropriate place to mount the first monographic exhibition of Carlo Crivelli (c.1435-1495) in this country than the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston, because its “St. George Slaying the Dragon” (1470), acquired by Mrs. Gardner in 1897, was the first Crivelli painting to enter an American collection. She purchased it at the urgent prompting of Bernard Berenson, who wrote to her that it was a painting “which at the bottom of my heart I prefer to every Titian, every Holbein, every Giorgione” (11; the cover image is a detail). Although Berenson later tempered his early enthusiasm for the painter, his admiration did not substantially wane; for certain methodological reasons, he does not include him in his classic “The Italian Painters of the Renaissance” of 1952, but he does pay him due tribute as one who “takes rank with the most genuine artists of all times and countries” (11). Those methodological reasons for marginalizing the artist are very clearly discussed by the exhibition’s co-curator and catalogue editor, Stephen J. Campbell, Wiesenfeld Professor of Art History at Johns Hopkins University. In his introductory essay “On the Importance of Crivelli,” he says it is a question of the direction art historiography took around the turn of the last century and its program to equate Italian Renaissance art primarily with the art of Florence, Venice, and Urbino, or at least to valorize artistic production in those centers at the expense of local currents and traditions in more peripheral areas of the peninsula. To a scholar like Berenson, Prof. Campbell points out, geography was destiny, and the fact that Crivelli, although born in Venice, worked primarily in the Marches, necessarily consigned him to the cultural outskirts and seriously compromised his historical standing. But, to put it plainly, that was no failure of Crivelli’s; it was rather the failure of scholarship to develop historical criteria appropriate to understanding him and other painters in similar situations (abetted by Giorgio Vasari’s omission of him and many others from his “Lives of the Painters”). Berenson was finally forced to acknowledge that “a formula that would, without distorting our entire view of Italian art in the fifteenth century, do full justice to such a painter as Carlo Crivelli, does not exist” (11)—which meant that, rather than adjusting the formula to include Crivelli, it was easier simply to toss him out of the whole equation. And so the artist has remained generally outside the Renaissance canon and not well known to the public, and, apart from a couple of occasions in Italy, he has never before had an exhibition of his own.“St. George” is joined here by twenty-two paintings and Crivelli’s only extant autograph drawing, loans from museums in the US and Europe that demonstrate clearly that the Italian Renaissance was stylistically more diverse and geographically more widespread than either contemporary or modern accounts generally indicate, and that certain notions of Gothic and Renaissance dear to art history still need seriously to be challenged. (This is the second such collaboration between the Gardner and Prof. Campbell; in 2002 he curated the museum's first ever monographic exhibition of Crivelli’s contemporary from Ferrara, Cosmè Tura, a painter whose visionary and fantastic imagery accorded just as little with the quattrocento Florentine paradigms as Crivelli’s.) The exhibition items are beautifully reproduced in the catalogue, with the panels from the reconstructed early polyptychs illustrated separately. (Only one of those polyptychs has survived intact in its original frame, the others having been disassembled into individual panels and predella scenes and widely dispersed in the nineteenth century to capitalize on a short-lived craze for the artist’s work.) These are extremely unusual and interesting paintings: beautifully colored, razor-sharp in drawing--“as if by lightning,” as Berenson put it--but one sees immediately what he meant by Crivelli’s formula-busting eccentricity: wrenched, idiosyncratic and amusing plays on perspective, disorienting and hilarious trompe-l’oeil effects, obsessive attention to detail and a van-Eyckian insistence on microscopic accuracy, etc.—these are features broadly characteristic of his painting and perfectly exemplified by his best-known picture, "The Annunciation with St. Emidius" (1486; National Gallery, London), an amazing interplay of surface ornamentation and perspectival illusion. Many of these features would seem to locate him historically a few decades earlier, and in general one senses a more tenacious remainder of the "International Gothic" in him than in most of his contemporaries: the exclusive use of tempera on panel (some transferred to canvas), the brocaded gold background, the devotion solely to religious painting, the preference for the polyptych over the “pala” or single-field altarpiece, etc. These are no doubt the effects of the conservative patronage of the monastic orders who were his primary employers. He was not a “progressive” painter, but—and this is a major scholarly point of the exhibition and catalogue—just because he was not helping to blaze the trail to Cézanne does not mean that he was stuck in a blind alley in some benighted backwater. One simply has to understand that his priority in painting was not representation or imitation, but, as the title precisely puts it, ornament and illusion--sometimes going even so far as to pull painting in the direction of sculpture. For example, one of his favorite techniques was “pastiglia,” the process of building up layers of gesso on the panel and carving them to create shapes projecting from the surface—or even casting gesso in prepared forms and gluing the pieces onto the panel—and then painting or gilding them to produce the effect of a very low relief somewhat akin to, although far more precise than, a heavy impasto in oil. (In the cover image, the hilt of St. George’s sword, his armor, and the studs along his horse’s bridle are done that way, but unfortunately the catalogue does not show any such passages in raking light to give the viewer a better sense of the depth of the relief, a disappointing omission given how important the technique was to his facture and how often it is mentioned in the texts.) This is just one instance of the tremendous richness of surface treatment in these paintings, which Prof. Campbell calls “unparalleled in contemporary Italian painting” (155).Apart from his excellent introduction, there are several other scholarly contributions by Renaissance specialists. They discuss such topics as his unusually extensive use of gold and highly ornamented textiles; the signature cucumber that persistently pops up as part of a fruit garland or a trompe-l’oeil device; the nineteenth-century recovery of the “Crivellischi” as Italian “Primitives”; his reception in the US; etc. Although a couple of the essays are not as free of scholarly jargon as one might wish, they are mostly interesting and informative. Each catalogue entry is provided with full curatorial data including provenance and dedicated literature and is accompanied by several signed pages of annotated discussion. Apart from these entries, most of which are reproduced full-page, there are also ninety-six very well chosen supportive illustrations in color, some of which are also full-page, and several pages of full-bled enlargements. There is no index, but a very good selected bibliography. The exhibition is a unique—no doubt once-in-a-lifetime—opportunity to experience these paintings together in one venue. It is on view from October 2015 until January 2016, but those who can’t see the show in person can be assured that the catalogue is a faithful reproduction. In addition, it registers several corrections to the information contained in the most recent major study, Ronald Lightbown’s big 2004 monograph, and I warmly recommend it to anyone wishing to take an instructive and entertaining side excursion off the beaten path of Italian Renaissance art.

P**O

A fresh look at a neglected Early Renaissance master

I read this book to bone up on the exhibit at the Isabella Stuart Garner Museum. It's ideal for such a purpose, both full of information about the artist's production and presenting individual write-ups on the works in the exhibit. But anyone interested in Early Renaissance art, and Crivelli in particular, should find this book rewarding.It discusses, among other things, why art historians have written Crevelli out of the history of Renaissance art; what caused his sudden brief popularity at the turn of the nineteenth century, particularly in America; what techniques and materials Crivelli used to achieve his gorgeous effects; the symbolism of his often idiosyncratic iconography; how local church and civil politics influenced his work; how and why the textile aesthetic influenced Crivelli; and how Crivelli created his illusions, both realistic and otherworldly.The essays by art experts are rich in original insights, but you do have to work for them a bit because most of the authors are fond of academic jargon. My favorite author among them, though, did manage to be lively as well as scholarly. His witty essay explores the significance of Crivelli's grotesque cucumbers!The color illustrations are good quality. The details in particular, highlight the beauty of Crivelli's sumptuous surfaces.Little is known of Crivelli's life, but I was fascinated to learn that he was imprisoned in Venice and exiled for abducting a sailor's wife. Later in his career he was knighted, so it seems he suffered ups and downs in his personal fortunes, as well as vicissitudes over the centuries in his artistic reputation.I've always liked Crivelli. But after reading this book I have a new appreciation for him.

M**A

readable, good reproductions

I appreciated the detail views of the reproductions. The text was not too dry as it can be with catalogs. The quality was good and it was reasonably priced.

O**H

Very happy with this book

Outstanding review of a relatively neglected painter and his place in the Italian Renaissance. The illustrations are very well reproduced and the text is enlightening. Very happy with this book.

Y**M

My personal discovery

I got recently introduced to Carlo Crivelli work in Milan and was amazed by his technique and originality. This catalog was the only book on Crivelli legacy I found and I'm happy to have it.

Y**V

Great little book - brilliantly published and presented

So far the best book on the subject. Great quality of prints and entertaining text. What else one could wish for from the catalogue...

A**R

The pictures were nice but the book is based around the title 'Ornament ...

The pictures were nice but the book is based around the title 'Ornament & Illusion' so for the purpose I bought the book, it did not fulfil my needs.

W**Y

Four Stars

Beautifully produced, though with a few odd gaps

M**7

Excellent catalogue

Superbly produced, great illustrations and first rate scholarship. Exactly what an exhibition catalogue should be.

S**N

Carlo Crivelli - great monogram on his work

A much under-rated artist, this is one of the few monograms on his work and as such is brilliant.

Trustpilot

1 month ago

2 weeks ago